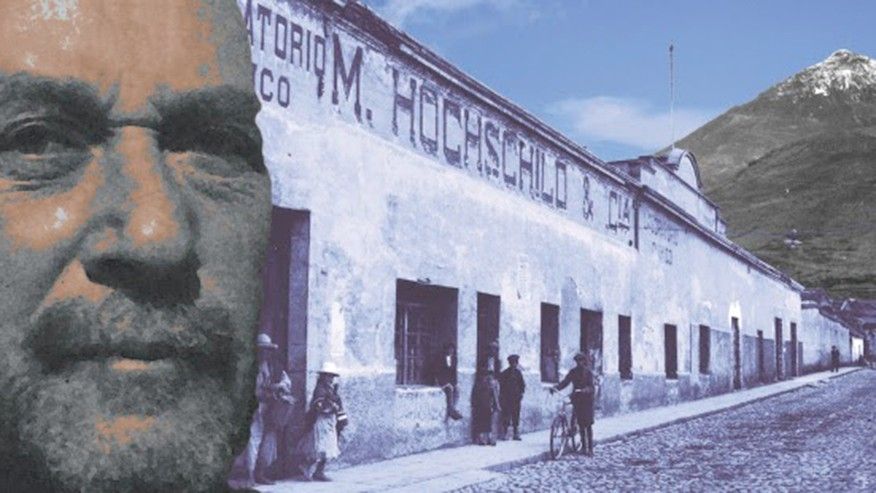

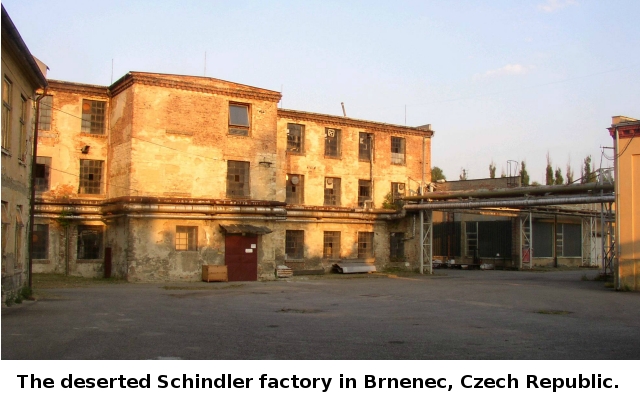

A plan to turn the deserted factory of famed German industrialist Oskar Schindler, who protected Jews from extermination during the Holocaust, into a museum is in jeopardy, due to financial difficulties and opposition in the Czech village where it is located, the UK's Guardian reported on Tuesday. In addition to the estimated cost of more than $5 million to convert the factory into a museum, the endeavor has also drawn resistance from residents of the village of Brnenec

Jaroslav Novak-the head of the Shoah and Oskar Schindler Memorial Endowment Memorial Foundation-was quoted by The Guardian as saying, "This is the only Nazi concentration camp in the Czech Republic that is still standing in its original building. You cannot allow it and the whole history of Schindler to disappear. I have been fighting for this for 20 years. But people are just not interested in it." The factory is where, in 1944, Oskar Schindler brought 1,200 Jewish workers and was able to keep them safe until the end of World War II-a story portrayed in director Steven Spielberg's 1993 Academy Award-winning film "Schindler's List." Opposition was explained by the Guardian as follows:

The industrialist was a Czechoslovakian citizen from the then mainly German-speaking Sudetenland region who spied for the Abwehr, the Nazi foreign intelligence service, before the territory was formally annexed by Hitler under the 1938 Munich agreement, and who later joined the Nazi party. Few Czechs had heard of his later wartime exploits before they were depicted by Hollywood. Even today, many recall Schindler, who died in 1974 and is honored along with his wife, Emilie, at Jerusalems Yad Vashem Holocaust Museum, by referring to his prewar local reputation as a "gauner" (German for crook) who was notorious for heavy drinking, womanizing and gambling debts.

Jitka Gruntova-a former Communist MP and author of a book about Schindler-was quoted as calling him "a traitor and a war criminal."

"I have found no evidence of Schindler saving prisoners," she said. "I've come to the conclusion he was only saving himself-mostly by writing a postwar synopsis of his alleged activities. I don't doubt there are certain witness statements in his favor but these are, as far as I can tell, made by people who belonged to the inner circle around him."

Historian Radoslav Fikejz chalked such skepticism up to expulsion of German-speaking Czechs after the war and the decades of one-party Communist rule the country experienced between 1948 and 1990.

"It's a very big problem because we still have 40 years of communism in our mentality," Fikejz told The Guardian. "It's also a problem that Schindler was a Sudeten-German and people are afraid of one question, which is: what happens when the Germans come back? But this is unrealistic. Yes Schindler was a Nazi, a war criminal and a spy. But I have met 150 Jews who were on his list and were in the Brnenec camp and they say that what's important is that they are alive."

Tomas Kraus, the director of the Federation of Jewish Communities in the Czech Republic, told the Guardian, "It's a very complex story. Schindler was a perpetrator who later became a savior and a hero. But he was not alone in that. There were others like him-he was only the most famous."